The first time I heard the word Zionism was August 1991, my first week of college at Binghamton University. (Please note that this is part one of two.)

Before college, I had been raised in a small rural town in central New York state.

A town of 8000 souls, Norwich was very white and very Christian— protestant, to be specific.

We had an exceedingly small Jewish population. Our Jewish Center, the only synagogue in the county, shared regional Rabbis for monthly services and holidays.

[Jumping the timeline - a note that in 2008, three young teens vandalized the interior of the Jewish Center in Norwich.]

I was in middle school, 1985, before I personally knew anyone who was Jewish.

I was rolling up my Snoopy sleeping bag for a sleepover at a new friend’s house when my mom said, casually, “Julia [not her real name] is Jewish, you know.”

Mom said this in the breezy tone she adopted when flagging something out of my ordinary: something that might carry an out-sized cultural weight that my young self was likely to sense but not understand.

To give you an idea of growing up in Norwich in the 70s and 80s, this breezy tone was also the tone Mom also used for things like:

a rumor that a favorite teacher was gay,

a friend having an outhouse instead of an indoor bathroom,

a caution that a friend’s parent was known to be a volatile alcoholic,

letting me know that her friend was likely to openly breastfeed her infant.

And, no, I hadn’t known this new friend was Jewish.

I stared at my Snoopy sleeping bag. My stomach fluttered with the usual nerves of an anxious kid, but something else, too: trepidation, fear of the unknown.

What did it mean to be Jewish? Would Julia’s family do weird things? Eat strange food? Make me say prayers in a different language?

What I knew about Judaism up to that point came from two sources: (1) my brother’s interest in World War II and (2) my sporadic Sunday School attendance at the United Methodist church.

This meant that the sum total of my knowledge was:

World War II had Nazis. Nazis murdered murdered millions of Jews in horrific concentration camps.

Judaism was the religion of Jesus of Nazareth.

Jews had the same Ten Commandments as Christians.

We had the same Bible — except the Jesus parts.

We were all somehow all children of Abraham and Moses. I thought. Unclear.

One of our Sunday School crafts was making paper mezuzahs.

Jewish people wore little circular hats when they went to their temple. (I had not witnessed this personally; I don’t know how I knew this. A TV show? Maybe Fame? I loved that show, and it introduced me to the “melting pot” of NYC.)

My sleepover unease dissipated as soon as I arrived at Julia’s. My new friend and I sat cross-legged on her bed and had what seemed at the time, and maybe could still be considered, a deep conversation about our religious beliefs and traditions.

Julia described her recent Bat Mitzvah. I described my recent confirmation.

Both had involved religious classes and a ceremony. Mine had involved a canoe trip with my religious leader; hers hadn’t. She had gotten a lot of presents; I hadn’t. Upsides, downsides.

Anyway our respective religions quickly became Not a Big Deal; it was just one part of who we were. In some ways it was important, but also, it became mundane. We both believed in God, we enjoyed our holiday traditions, but neither of us were strict or dogmatic. It felt interesting and comfortable.

Same with the other Jewish friend I had in high school — I’m not kidding, only one — not because I was discriminating but because of the population of Jewish families. Like I said, Norwich was white and protestant.

Judaism was part of Paula’s [not her real name] life but in the same way church was part of mine. Sometimes we went to services, sometimes we didn’t. We gave each other Hanukkah or Christmas presents. But way more important to us was the teenager stuff: crushes, parties, homework.

To teenage me, the biggest difference between being Christian and being Jewish was antisemitism and the holocaust.

Norwich was a politically conservative town. When I was growing up, racist and antisemitic “jokes” were common. (There was also a lot of anti-Catholic “humor.”) Many of my classmates and their parents let out a steady stream of pejoratives about ethnic or cultural groups.

Noteworthy: in the late 1980s, a specifically misogynistic stripe of antisemitism was making the rounds. It was the Jewish American Princess (“jap”) stereotype. I remember reading an article in one of my teenager magazines (Seventeen? Sassy? YM?) about the stereotype on college campuses. Female Jewish students at Syracuse University were being called this, shouted at during a basketball game. [I can’t find the specific article, but this one is contemporaneous.]

From what I could tell, it seemed bad to call anyone this name, but it was also confusing to me that my Jewish friends used the word to characterize people.

But nothing was confusing about the Holocaust.

Our social studies teacher rolled out the film projector to show us archival footage: skeletal survivors staggering out of liberated concentration camps. The dead piled in mass graves. It was unspeakably horrific.

Our teacher admonished us: This is terrible — and terribly important. To not know history is to repeat history.

Even in a conservative small town, these teachings were clear: the Holocaust was horrible, and unjust, a singularly terrible event in history. It must never happen again.

The first Gulf War started during my senior year of high school.

The U.S. invaded Iraq in January 1991. My teachers characterized it as the first U.S. war since Vietnam.

I was terrified. My father had been drafted into the Vietnam conflict. Did that mean there would be a draft for the Gulf War? Were my friends about to be torn from their families? Was my brother in danger? My boyfriend? I was haunted, terrified by the specter of conscription lotteries, friends coming home in coffins.

I asked a social studies teacher. Will there be a draft?

In another of many staggering moments of reckless miseducation — this one sent me spiraling into a cascade of panic attacks for MONTHS — my social studies teacher nodded confidently. “Oh yeah. If there’s a war, there will be a draft. Count on it.”

My stomach roiled. How would I save my friends?

A different teacher, one who was Twelve-Step sober, relatively liberal, and Jewish — the only openly Jewish teacher I’d had — was equally confident of his assertions, but a tad more accurate. He pounded his lectern to punctuate every syllable:

Israel is handing out gas masks to its citizens.

Do you understand the implications of that?

The only democracy in the Middle East! America’s closest ally! They are handing out gas masks!

What do you think it would be like to be Jewish, to be in Israel, to be the survivors of the Holocaust — mass murder perpetrated in gas chambers? To be handed a gas mask by your government?! Because Saddam Hussein might gas you?

I took this to heart.

Every point.

School, TV news, and the newspapers told me this war was about freedom and democracy.

It also told me:

Israel was the sole outpost of democracy in the region and it needed protection. The equation I learned, reinforced over and over, was that Israel = Jews. Judaism = Israel. And Jews are always the underdogs. They were the victims of the worst historical atrocity on record, and these atrocities could be repeated at any moment by bad leaders, leaders who always, always looked and sounded Arab.

The other equation: Arabs are the bad guys. Always. Anti-Arab prejudice was so present in my entire ecosystem that asking me to describe anti-Arab bias would have been like asking a fish to describe water.

I never, not ever, saw a positive or even neutral depiction of an Arab —or Muslim, for that matter— person. Not in the news, not in the media. The way the news and my teachers talked about “Moslems” or “Arabs,” they were always other, savage, dangerous. The movies? Media? Are you kidding? Have you watched Back the Future Recently? Indiscriminately violent “Bad Arab” terrorists (“The Libyans!”) shoot down Doc Brown and become the reason Marty McFly jumps into the time machine in the first place.

My gut, my innate desire for justice and peace and fairness told me other, conflicting things:

It really seemed like this war was actually about U.S. access to oil, even though nobody around me was saying this.

I must figure out how to help people dodge the draft. Even though another social studies teacher had lectured us that Jimmy Carter’s pardoning of draft dodgers was one of the top five worst things that any U.S. president had ever done, tantamount to treason. I felt deep in my bones that a draft was not ok. (Spoiler alarm: there wasn’t a draft.)

Onward, to college.

SUNY-Binghamton was about an hour from Norwich, but it was a different world. It was stimulating, intellectual, fun. Everyone was smart! Lots of students were from “the city” or “downstate.”

I was excited to meet new folks from different backgrounds.

SUNY-B had a relatively large population of Jewish students.

The count in 2024 is that 26% of its undergraduate students are Jewish, giving SUNY-B the third highest percentage of Jewish students of public universities in the U.S. after CUNY-Brooklyn (38%) and Queens College (another CUNY, 31%).

My curiosity has always been nearly insatiable.

I loved hearing people’s stories, still do. Everyone seemed so much worldlier than I was.

I heard about trips to Israel.

I learned the distinction between downstate vs. “the city” vs. Long Island vs. Queens, The Bronx, Manhattan.

I learned the difference between Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox Judaism.

I learned Jewish folk dances, walked a new friend to Hillel, and met up with dorm-mates after their meals at the KoKi (the Kosher Kitchen, located in the student union).

I quickly learned about Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur because SUNY-B had an early fall break for the High Holy days.

I tried delicious food that was introduced to me as Israeli: hummus, pita, feta, falafel. (Not until this year did I begin to learn a more robust truth about Israeli cuisine.)

In short, and in short time, Judaism became a big part of my everyday life.

And that’s how I learned about Zionism.

My across-the-dorm-hall friend Michelle [not her real name] was from Tel Aviv by way of Brooklyn.

She told me about being in Israel during the Iraq War.

She had, indeed, been issued a gas mask.

I thought it was badass of her to stay there during the war.

“I’m not a religious Jew, though,” Michelle said. “I consider myself culturally Jewish.”

“Cool,” I nodded.

“And I’m a Zionist,” Michelle said.

“What’s a Zionist?” I asked.

“It’s someone who thinks Jews should have a homeland. Where Jews can always be safe.”

“Ah. Like Israel,” I nodded. (I felt proud to know this.)

“Right. Like Israel. The biblical homeland of Judaism.”

This made sense to me at the time. I had taken note of the maps in the front of bibles.

There were a couple of blips in the logic of Zionism that did puzzle me at the time:

How does ‘biblical homeland’ make sense as a reason for Zionism if you’re [Michelle, specifically] not religious and don’t “believe” in the bible?

How can anyone possibly prove, or argue with, [my religious friends’ belief] that Jews are “God’s chosen people”? Doesn’t every religion think they are God’s chosen people?

But I waved away the cognitive dissonance.

I waved it away because I figured my confusion was probably due to not knowing enough about the whole situation. After all: my people hadn’t been subjected to genocide in the Holocaust. Jews were the experts, so I should take Jewish people’s word for it.

I also waved it away because I’d been told by U.S. culture, public school, and every source of media I had ever been exposed to, that the existence of Israel was essential for the safety of the Jewish people.

Note some characteristics of my introduction to Zionism:

The person who first introduced me to Zionism, and who called herself a Zionist, was not religious. She did not keep kosher; she did not attend religious services or observe religious practices. This made her one of the more relaxed-about-being-Jewish friend on my floor. Thus I equated Zionism with a relaxed, progressive, cultural-but-not-necessarily-religious, Judaism.

It made sense to me that Michelle, and others, said there should be somewhere safe for Jews. Of course there should. Everyone should have a safe haven — and particularly victims of a genocide like the Holocaust.

There was no mention whatsoever of people already living on “Israeli” land. Zero. Nada. Zilch. None. I literally—and I mean literally—thought that Israel was “a land without a people for a people without a land.”

My Zionist friend Michelle was cool and brave. She stayed in Tel Aviv during the Gulf War, even when she had to carry a gas mask. She was smart, feminist, and progressive. She introduced Zionism succinctly in a way that felt like basic facts.

All my Jewish friends were Zionists. And these weren’t mere acquaintances. Many became dear friends. One became my BFF. Zionism just felt like something that went along with being Jewish. Judaism, Zionism, Israel: they were inextricably linked.

And that was just how it was.

And maybe how it would have continued to be.

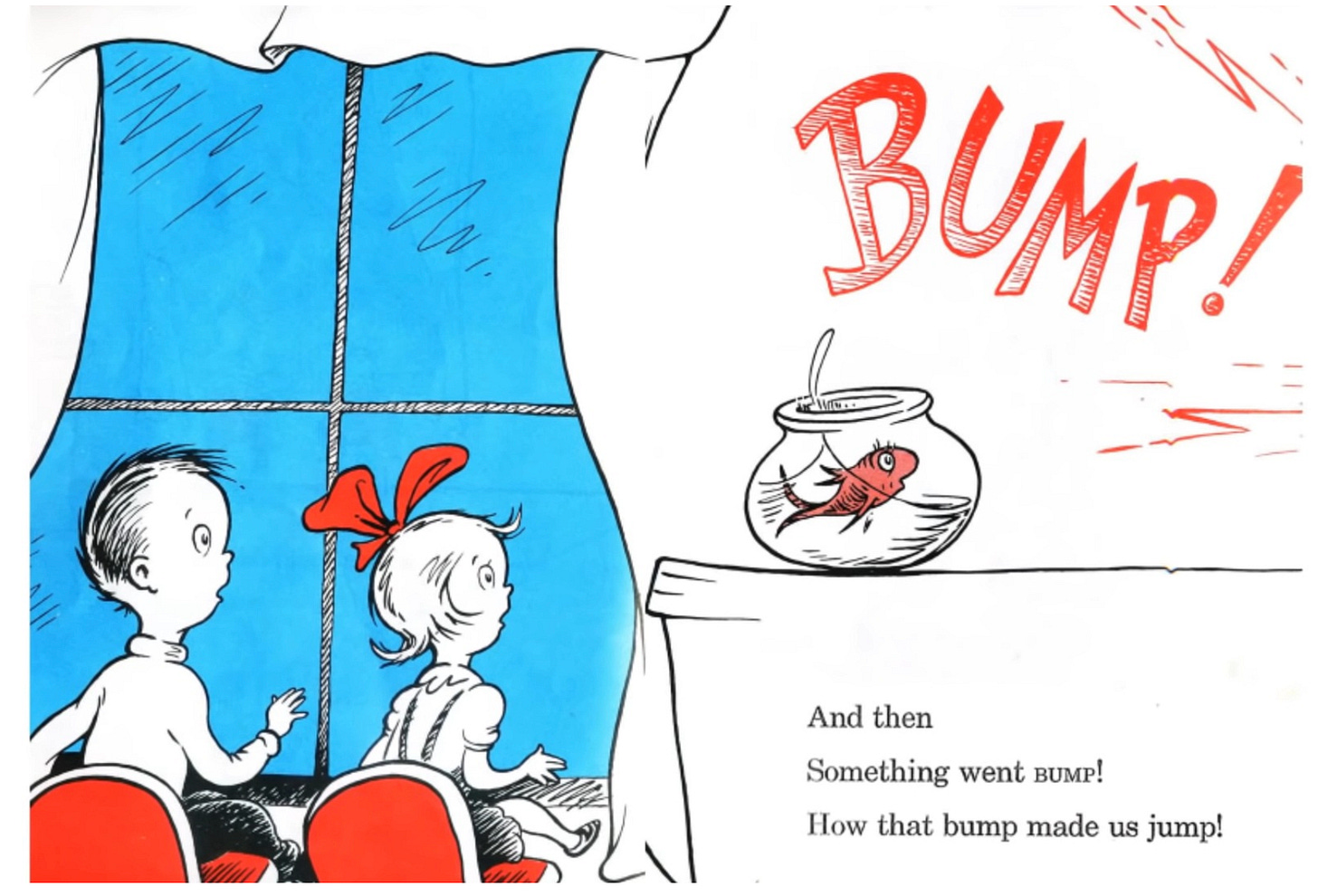

Until, about seven years after my introduction to Zionism, something went BUMP!

How that bump made me jump!

TO BE CONTINUED. Next time on Unruly Quaker, we’ll talk about those bumps. And my jumps.

XOXO

Thank you for sharing your fear of a possible draft! I shared in it. My male American exchange student friends and I discussed this possibility in our meeting place, a bar in our host city Liege, Belgium. We were afraid that even an ocean away from the US government we might be drafted.